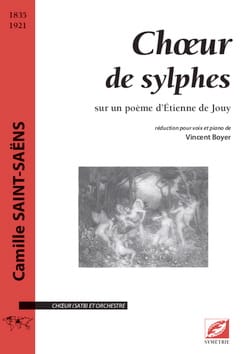

Far from being an isolated work in the work of Camille Saint-Saëns, the Sylphes Choir belongs to a small ensemble made at the beginning of his career in the particular context of the competition for the Prix de Rome. Established in 1803, suppressed in the wake of the events of May 1968, it was for more than a century and a half the most coveted French musical composition awards. Organized by the Institute, it guaranteed to its laureates, for lack of the insurance of a future career without pitfalls, at least the entrance by the big door in the artistic world and some years of pension in Italy, to the villa Medici. In fact, very little resisted the attraction of this reward likely to mark brilliantly the culmination of long years of study. That a personality like Saint-Saens has presented itself is not surprising. But although called to become at the turn of the century one of the most illustrious representatives of academic art, he never got, despite two participations, the famous first grand prize. The competition was then organized in two separate events: the first, eliminatory, consisted of the realization of a fugue and a choir with orchestral accompaniment on a given poem, the second in the composition of a great cantata for three solo voices. Saint-Saëns himself wrote two, The Return of Virginia (1852) and Ivanhoe (1864). It was between June 5 and 11, 1852, for his first participation in the contest, that Saint-Saëns composed the Sylph Choir. Favorably received, he allowed the musician to be placed at the top of the six candidates admitted for the final round. But it is true that objectively the proposed poem had everything to enable it to shine. From a libretto by Étienne de Jouy and Nicolas Lefebvre, Zirphile and Fleur de Myrte, already set to music by Charles-Simon Catel (1818), the extract chosen (Act I, Scene 4) was particularly adapted to the 'exercise. In a few firmly drawn pages, Saint-Saëns manages to transcribe the wonderful atmosphere, all lightness, of the world of the spirits of the air. In many respects, the result is reminiscent of the "Scherzo" of Mendelssohn's Dream of a Summer Night (1843), a composer to whom he devoted a cult. Certainly, like all youthful works, the Sylph Choir was written under influence. In the perspective of the Prix de Rome, the piece was also designed to meet various requirements that some denounced in principle as pastists. Beyond these reservations a little simplistic, the book is nonetheless an example of the great French academic tradition and its ideal of elegance and clarity. Behind his undeniable mastery of form and writing, the author reveals a work that, without being revolutionary, contains undeniable beauties.

| |

|